Background

The March 2023 White Paper on Artificial Intelligence, which we reported on here, introduced us to UK’s approach towards regulating artificial intelligence (“AI”) through existing regulators considering the impact of AI within their respective remits and considering whether guidance or legislation may be needed in their respective areas. Fast-forward six months and the Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”), UK’s competition and consumer protection authority, published its initial review of AI Foundation Models (“FM”) which looked at competition and consumer protection issues, acting as a starting point in establishing CMA’s regulation of AI.

It is a comprehensive, 128-page report (which you can find here) which covers development of FMs, barriers to entry, consumer protection and the current legal framework. The report focuses on the CMA’s views on barriers to entry, impact of FMs on competition in other markets, as well as consumer protection issues.

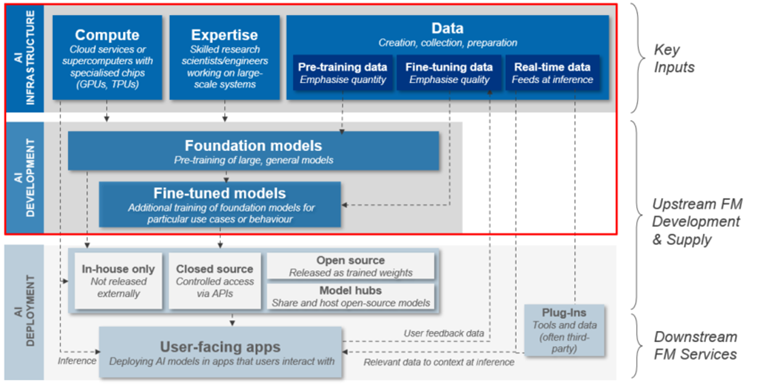

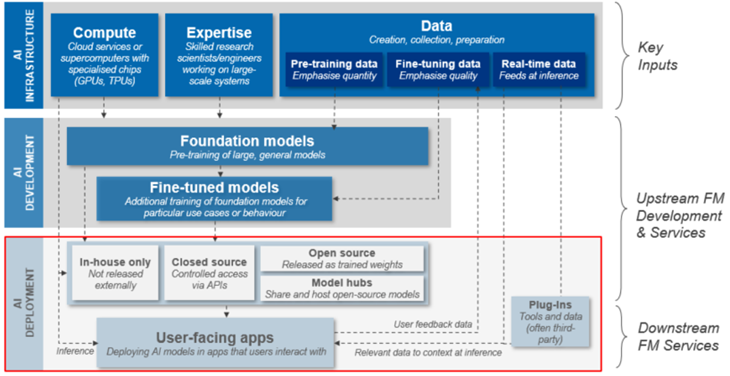

The report defines FMs as a “type of AI technology that are trained on vast amounts of data that can be adapted to a wide range of tasks and operations.” FMs include large language models (LLMs) trained on text and images, such as the models powering ChatGPT, and models trained on video, audio and 3D environment data that are still in research phase.

Competition in the developments of FM

The CMA, led by views from experiences of previous technology-driven markets, that network effects and switching barriers result in stifled competition and a “winner-takes-most” outcome, assessed the applicability of these factors to FMs in order to evaluate the likelihood and potential of entry barriers and weak competition.

Access to data

The report states that the data used at each stage of FM development risks raising the barriers to entry. Whilst FM developers today can rely on publicly available open-source data for pre-training (pre-training is the first stage of building knowledge of the model by using hundreds or thousands of gigabytes of data), it is estimated that these sources are likely to be fully exploited within the next three years. This could increase reliance on proprietary data (privately owned or licensed data) which may create an advantage to companies with large financial resources or those already generating data in their primary and other digital markets. The report singles out YouTube as a particularly valuable source given its repository of “conventional style” video data with accompanying text and metadata.

Infrastructure costs

Computing resourcing costs, particularly of accelerator chips are flagged as a significant risk. In an accelerator chip market with a supply shortage and issues around efficiency, companies other than NVIDIA and Google are struggling to compete. For example, none of the three largest cloud service providers in the UK have access to market-leading NVIDIA A100 model. Microsoft and NVIDIA’s FM has an estimated compute cost of $100M and such infrastructure costs are cited by the review as one of key reasons why users of FM may not choose to develop their own. Companies can turn to cloud service providers, who may in turn prioritise partnerships and resources to more established clients with greater commercial potential.

Open-source models

An open-source model is a decentralised development model which encourages collaboration and modification through an “open-source licence”. Such models are typically more transparent and accessible than their closed-source counterparts. The CMA’s perceived risks with open-source models relate to their decentralised nature and associated challenges surrounding governance and harmful application. Open-source models, however, tend to be smaller and perform worse than best closed-source models. There are further uncertainties about the ability of open-source developers to secure funding, given the lacking appetite of investors.

The impact of FMs on competition in other markets

New and changed markets

FMs have the potential to create new industries and shake existing ones by allow companies of various shapes and sizes to improve productivity and efficiency. For example, in creative sectors such as marketing, FMs are being used to produce content which enables emerging companies to compete with established players. The CMA lists three ways in which companies engage FMs, namely; developing a FM in-house from scratch; partnering with a FM provider to enhance an existing FM; and, adopting a third party plug-in. Third party plug-ins are the most common applications of FMs in the market today, thanks to lower set-up costs and ability to integrate within existing infrastructure. However, report is inconclusive regarding the impact of FMs on disrupting current market conditions.

Vertical integration

The report flags that developers and suppliers of FMs often offer related services themselves, creating a vertically integrated ecosystem in competition with downstream parties. Such an ecosystem may be convenient and highly customised for end users, based on vast amounts of data collected about that user. On the other hand, the CMA is uncertain as to whether consumers will prefer access via a single or multiple access points and providers’ ability to “lock in” consumers through effective customisation and data portability.

Secondly, depending on how FM monetisation strategies evolve, the CMA flags concerns about vertically integrated companies applying restrictive practices, such as dual competitor relationships between vertically integrated suppliers and their downstream customers. This is likely to be impacted by the ease of developing FMs in-house, availability of plug-ins and access to funding.

Downward market features impacting FM development

Based on the CMA’s observation of other digital markets, the downward FM market can exhibit structural features which can restrict competition in upward FM development. Some of these features include:

- Economies of scope – this could raise barriers to entry for new entrants active only in one of few FM services, because cost-related economies of scope would enable companies to spread the cost of developing a FM across a number of services.

- Switching costs – Customisation of FMs might make it difficult for consumers to switch between providers.

- Existing customer base – such adopters of FM services can encourage greater take-up by linking FM services with existing products, creating an easy way for consumers to try new FM capabilities.

Consumer protection risks

Exacerbated existing consumer harms

The CMA reports that FMs have the potential to enhance consumer risks that are already commonly associated with emerging technologies and the internet. These include:

- Fake reviews – use of FMs is likely to make it cheaper and easier to create fake reviews. Content generated is becoming more convincing, therefore it may be increasingly difficult to decipher between a genuine and a fake review. The CMA is unclear at this stage whether FM tools are capable of helping users to better identify fake reviews when they arise.

- Phishing – FMs have the potential to produce even more convincing and personalised content at scale, making it even harder for consumers to know whether they can trust the communications they have received.

Hallucinations and consumer understanding

The report hints at FMs “faithfulness”; its output being inconsistent with the user’s prompt, and “factuality”, that is, consistency with real-world knowledge. These faults are commonly known as FM “hallucinations.” Hallucinations tend to happen due to spurious correlations between training data, models mixing facts between similar observations and models losing reliability due to conversation history or bias towards using information learned during training. This is applicable across FMs and commonly found even amongst best performing models such as GPT-4 which, according to the report, can generate hallucinated content in around 11.4% of user queries. CMA points to human evaluations as the “gold standard” in evaluating hallucinations.

Further, the report shines light on consumers overconfidence with FMs, referring to a study which detects that whilst people detected deepfakes 42-77% of the time, they reported confidence in their judgment 73-85% of the time. The same trend was found by OpenAI, the makers of ChatGPT, who in 2019 found that humans were able to tell the difference between human written and FM written articles about 52% of the time. Similarly, a study found that only 52% of people in the UK have heard of generative AI. Consumers may disregard warnings about limitations of FMs and place disproportionate reliance on them if they do not know what generative AI is in the first place. Secondly, receipt of false and misleading information is likely to deter users from adapting FMs in the long term.

Competition and consumer protection law

Interestingly, CMA posts warning signs to businesses, flagging its “likely interest” in mergers and acquisitions involving FMs that may harm competition. It does not list specific sectors or criteria; thus it serves as a broad reminder to the market about CMA’s focus on FMs, who encourage parties involved to inform them of the transaction.

The CMA, in the report, interprets the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (CRA) to place an obligation on a business to comply with CRA requirements when contracting with a consumer, regardless of whether that business developed the FM itself or uses a third party adaptation. The review also touches on the application of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations (CPRs) to businesses which supply or licence FMs for use by other consumer facing businesses. In such cases, where B2B practices can fall within the CPRs if they have a direct connection the promotion, sale or supply of goods or services to a consumer.

Our spin

The CMA has plainly applied a lot of thought to the topic. However, things are so uncertain that no one know whether FMs will have a huge impact on markets or not. We would expect that the CMA will pay particular attention to any mergers or other issues that come up involving FMs. They will want to be seen to be ahead of or at least close to the curve.

unknownx500

unknownx500